Deep Sky Astrophotography in Moonlight

March 23, 2014

The Moon is full about every four weeks. That’s a given, like snow in winter where I live. Within about a week either side of full, the Moon floods the night sky with reflected sunlight. This can be, among other things, beautiful, romantic, eerie, tranquil or even photogenic in its own right. But it creates real challenges for deep sky imaging.

Much like man-made light pollution, the Moon’s light washes out faint objects. Since I’m not willing to surrender two weeks of deep sky imaging to the Moon every month, I’ve developed a few strategies to keep the shutter open even when the Moon is big and bright.

Location, Location, Location

When the Moon is 3-7 days on either side of full, I can usually find some pretty dark areas of sky in the north, especially on very transparent nights when there are fewer particles in the air to scatter moonlight. The moon follows a lower altitude path in the summer than winter, so is further away from my northern target area in summer than in winter (but the nights are so short!).

Choose Star Clusters

Open clusters and globular clusters are my targets of choice during this time, especially if I want to acquire a whole colour image data set in one session (I use a mono camera with filters). Since they are often overlooked by imagers, compared to galaxies and nebulae, this gives me a chance to give open and globular clusters their due in my image collection.

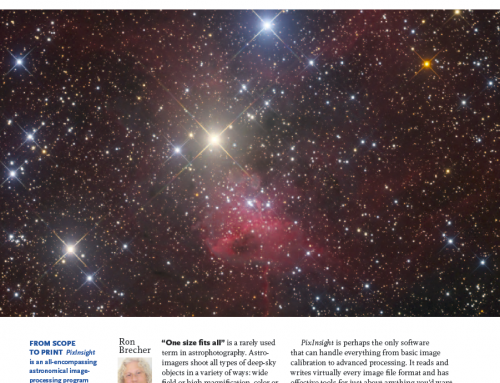

Colour data for this image of the Little Dumbbell Nebula was captured under moonlight. Luminance data was acquired near new moon.

Take Short Exposures

I have found that taking many relatively short exposures gives better results than fewer long exposures. I have found this to be generally true, but especially when the skies are bright from moonlight or light pollution. One reason is that shorter images have fewer (or no) saturated pixels in the bright areas. Another reason is that stacking more images does a better job of removing artifacts in individual frames, like hot or cold pixels. Finally, a lower background brightness in the image gives more dynamic range between the darkest and brightest pixels in the image.

Plan to Return Later

My colour pictures are made up of four or five channels, each taken through a different filter (red, green, blue, clear and sometimes Hydrogen-alpha). The R, G and B channels don’t provide much brightness information in the final image (that comes from the clear filter), so I often can collect colour data when the moon is bright, even for galaxies and nebulae. I can also get good H-alpha data in moonlight — even on the night of full Moon – because of the narrow range of light wavelengths that passes through my H-alpha filter. But I usually wait for a moonless night to shoot through the clear (luminance) filter, which provides nearly all the brightness information in my final image. A few days after full Moon, I can shoot Luminance data between the end of twilight and when the moon rises above the trees that shield my eastern horizon.

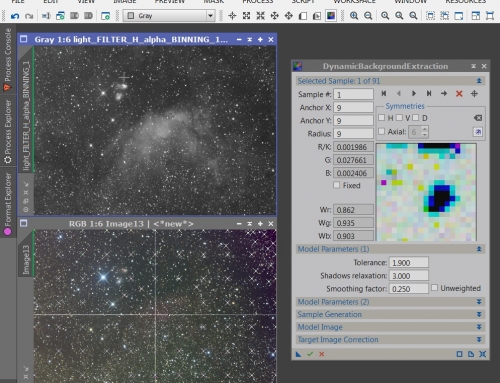

Moonlight gradients were easily dealt with by PixInsight’s Dynamic Background Extraction process in this image of NGC2419.

Remove Light Gradients During Processing

The reality is that even on moonless nights most of us will capture unwanted light pollution in our images along with the precious photons we’re really after. Most image processing software comes with tools that can reduce the impact of unwanted light gradients in images. My personal favourite is the Dynamic Background Extraction tool in PixInsight. Gradient Exterminator is an easy-to-use plug-in for Photoshop.

Tune-up Time

Telescopes, cameras and mounts need a lot of regular TLC to keep working at their best. The period around full Moon each month is when I tend to do these things. Even though I have a “permanent” setup, I change optics, camera orientation, and guiding parameters regularly. My scope’s collimation and my mount’s polar alignment and pointing models need to be periodically updated. New software configurations for imaging and mount control need testing. When the moon is out I sometimes take test shots to see how to best frame objects in future imaging sessions.

Overcome

Most amateur astroimagers know that there’s a sort of “Drake equation” for the probability of getting a good night’s imaging. And guess what: the news isn’t good. For most of us imaging time is very limited due to clouds, work, family commitments, other hobbies (really??), equipment malfunctions and even short summer nights. With a few carefully chosen strategies, you can stop the Moon from robbing half of your imaging time every month, and make sure you’re equipment is ship-shape for those moonless nights deep sky imagers crave.

And don’t forget to look at the moon with any size telescope or the naked eye. It is beautiful. It’s also a good first target for imaging with any kind of camera.

Thanks much for the article.

Thanks for your article its clear and insightfull …

I’m interested to hear about why you prefer shorter subs to longer ones under a bright moon or in light pollution, and also why you prefer them just generally. I recently upgraded to a guided setup, and I have light pollution, although much of that is removed by a good LP filter which I recently bought, and I can also remove some light pollution in Pix. I was hoping to go out the next few nights and try to capture some data but it’s going to be under a full moon, so I was considering star clusters rather than faint nebulas. I was just curious, do you really think that shorter subs are better than longer subs in all scenarios, and not just under a bright moon and/or light pollution? Having just upgraded to guided imaging (having been told that this is what I would need to do in order to capture the fainter targets), it would be disheartening to discover that actually lots of shorter (possibly unguided) subs might do a better job that fewer longer (guided) subs.

The “best” length of subs depends on a whole range of factors – brightness of the sky, focal ratio of the optic, quality of mount/guiding, etc., full-well capacity of the camera and more. Once a sub is long enough that the image is limited by sky quality rather than electronic noise, there is no advantage to exposing longer. More subs also give better results from stacking, since sigma clipping methods can be used. In other words, it is always a compromise. Try a few different times and see what you get. For myself, when shooting at f/6.8 I shoot 15m in RGB and 20-30m narrowband. At f/3.6, I’ve had great results with 2m subs. As for guiding, the need for this depends on mount quality, focal length, accuracy of polar alignment and exposure time. With my dslr at focal lengths from 24mm-100mm I do not guide, but I keep my exposures to 3m or less. Light pollution filters won’t do anything to help with moonlight, since the moon emits light across the visible spectrum. LP filters remove specific wavelengths. They have pluses and minuses too — particularly affecting colour balance. The upshot is that exposure should be long enough that the noise in the shot is limited by sky quality rather than camera noise. Longer than that doesn’t really add anything, and reduces the total number of frames for stacking. See https://starizona.com/acb/ccd/calc_ideal.aspx for more information. You’ll probably need longer exposures to get a sky-limited result if you are using a filter. Good luck!

Great info, thanks!

Excellent reading. Going to read again and again a few times actually! Thanks for sharing Ron. I should have read this article sooner as I believe I have seen you mention it a few times previously in image posts on subjects acquired during the Full Moon stretch.